How to Build a Great Remote Company Culture

One of the best decisions we’ve made at Help Scout is to build a remote culture.

The 75 people on our remote team hail from more than 50 cities in over 12 countries around the world. While the benefits of a remote culture are tremendous, being successful requires radical commitment from leadership on your team.

As a founder or manager, this isn’t a decision to take lightly, because it will undoubtedly make your job harder. Remote teams require more structure, better communication, and a high level of proactive transparency from you.

We’ve made our fair share of mistakes and learned a lot over the last seven-plus years. My goal is to share the most important learnings, along with the data, so you can apply at least one insight (whether you are remote or not) to your team.

Remote company culture

There are a number of reasons why I’m passionate about remote work, but the most important reason is talent. What’s most exciting to me in life is working with people who are a lot better than me and who force me to learn at a high rate. I can’t get enough of it, which is why I’m so fiercely committed to this way of working.

Think of it this way: Do you think more talent exists within a 20-mile radius of your office, or on planet earth?

Like a lot of other small businesses, Help Scout is in a market surrounded by companies with more influence, more people, and much greater resources. The only way we can win is to use constraints as an advantage, to invest in things you can’t write a check for, and to build a team of people who can punch way above their weight. Doing remote well gives us a considerable advantage that you can’t buy: We have access to people most companies don’t.

But access to a broader talent pool has to be earned. You have to build a company people want to work for and a culture people want to be part of. It’s been a journey, but our 2017 eNPS score was 81. Among women it was even higher, with a score of 87. Identifying and embracing a few key principles, along with a lot of hard work, enabled us to get to this point.

‘Remote first’ or don’t bother

I’m not a hard-liner who believes remote is the way every business should work. Let’s be honest: Each way of working (remote, co-located, multi-office or mixed) has pros and cons you need to be mindful of. It’s less about the philosophy and more about how well you can execute it.

That said, if you want remote company culture to be all or part of your culture mix, you have to be “remote first.” Remote culture has to be an inalterable part of your company’s DNA, which is why it’s hard for companies to change once they’ve chosen a way of working.

A culture’s effectiveness revolves around how information flows. Everyone needs to feel like they have access to the same information, but remote and co-located cultures share information differently.

For example, let’s take the common trap a lot of co-located cultures are falling into today, where they make exceptions for certain people to work remotely so they can dip their toe into the talent pool. This is a recipe for disaster because the company hasn’t changed the way they share information. Once someone goes remote, they miss out on information in impromptu meetings, on whiteboards, at the proverbial water cooler, and when grabbing drinks after work. Very quickly, they’ll feel out of the loop and unhappy, unable to do their best work.

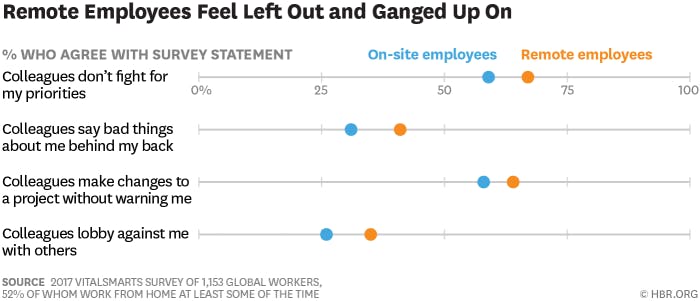

This study of 1,100 remote employees makes the point painfully clear:

When a company doesn’t change the way it communicates when the first person goes remote, it will fail to realize the benefits and likely alienate those people. And when it fails, the company will ignorantly blame the remote philosophy for being ineffective even though it’s their own fault. It’s like going on a diet, not changing any of your habits, then blaming the diet for not working.

At Help Scout we have two offices — one in Boston and one in Boulder. Neither has a kegerator, a ping pong table, a whiteboard, or office perks. Every room is wired for one-click video calls with teammates, and you’ll find the ambiance to be more like a library than an office. We do this intentionally, so that even in an office, it’s the same environment our remote colleagues have, with the same benefits.

What needs to change for a company to be remote-first? I could write a whole separate essay on this, but here are some of the key high-level tactics:

Managers have to work hard to build and maintain great relationships with their teams. It’s a lot harder being a manager in a remote culture than it is in a co-located one.

Most information needs to be written or recorded, available for people to consume it on their own time.

You’ll have to adopt a level of transparency that feels uncomfortable at first, so everyone feels connected with the business.

Overcome the “water cooler gap,” where people build strong working relationships through shared bonding, by forcing it with a number of strategies.

Most of your communication is written and you must be excellent at it. People who aren’t excellent written communicators will struggle on remote teams.

Hiring for remote teams

When Jared, Denny and I founded Help Scout, none of us had ever hired anyone. Ever. And it showed. Not only did we have a lot to learn about hiring, we also took too long to recognize a misalignment and part ways with people.

From 2011 through 2014, we hired 17 people at Help Scout. Eleven of them (65%) were eventually let go. Of the people we let go, their average tenure was 19 months.

From 2015 through April 2018, we hired 75 people, and only 13 (17%) of them have been let go. In 2017, the average tenure of the people we let go was 8 months, and has gone down every year since 2014.

I take 100% responsibility for every hiring mistake, but it’s still no reason to keep someone on the team who could be doing better work elsewhere.

Related: Help Scout's Ultimate Guide to Remote Management

So what did we learn? And for the love of all things, how can you avoid having to learn this the hard way?

Seek people in love with the work

The two things I look for when hiring for our remote team are:

a track record of excellence, and

a love for the craft.

We’re looking for someone who knows exactly what they want from their career, and who just needs a culture that will give them enough ownership to do their best work.

While I’d like to think of Help Scout as a collaborative environment, a lot of people on the team spend 4-6 hours heads down every day, working on hard problems. We need folks who can make the most of that time and require little to no direction to do great work.

Hiring aspirational candidates — people fresh out of school, or doing this type of work for the first time — doesn’t work well on remote teams. As much as we’d like to hire more junior folks and see them fulfill their potential, it’s much more challenging in a remote culture for both sides. Several of our early hiring mistakes had to do with hiring aspirational folks, who were great people, but who weren’t going to do their best work at Help Scout.

By not hiring aspirational candidates, we’ve realized the benefits of surrounding everyone with high performers who continue raising the bar.

Optimize for work-life harmony

Remote work skeptics often assume people work less when they aren’t going into an office. My experience has been quite the opposite. When you hire people who love the work, they might end up doing it for 12-14 hours before they even realize it. Obviously this isn’t sustainable or healthy, which is why we look for a high level of self-discipline and work-life harmony when hiring people.

Remote workers need things pulling them away from work, like family, hobbies, and other passions. When people are disciplined about maintaining work-life harmony, three great things happen: They don’t burn out, they do their best work, and they’re happy working at your company.

Related: Are Side Hustles Good for Business?

What if potential hires haven’t worked remotely before?

I’ve talked with a lot of companies who aren’t interested in hiring remote folks unless they’ve worked remotely before. I don’t understand that train of thought. If the person is qualified and excited about the prospect of working remotely, it’s your responsibility to make them successful. Have you ever heard of a co-located culture screening people based on whether they’ve worked in an office before? Of course not.

This isn’t a metric we actively track, but I’d estimate that roughly 50% of the people we hire haven’t worked remotely before. We’re still confident about hiring them because we believe we’ve created a culture in which they can be happy and successful.

How to hire remotely

As a result of our early hiring mistakes, we’ve put countless hours into refining the hiring process. Not surprisingly, as we got more thoughtful and structured, we made fewer mistakes. For all the details, be sure to check out our 12-step remote hiring process. That article is a great overview of the tactics, but there are also a few strategic adjustments that have made an impact.

Make remote part of your brand

From January through April 2018, 2,898 people applied for roles at Help Scout. Of that group, we hired 11, which is a 0.38% acceptance rate. For comparison, Harvard accepts 6% of applicants, and Google hires 0.2% of applicants.

It’s also worth noting that we only post our jobs on one or two highly targeted job boards (if any). We never use the larger sites, where you can easily get hundreds of unqualified applicants. The quality is quite high for the roles we post.

I say this not to brag, but to demonstrate the importance of making remote work synonymous with your brand. On this blog, you’ll find more than a dozen posts about all things remote. It’s clearly part of our DNA, something we’re passionate about, and it’s obvious to people considering a role with Help Scout. It’s taken seven years of investment to see this level of quality in our hiring pipeline.

Experienced remote people are well aware that the “remote first” philosophy must be adopted in order for them to be successful. If they don’t see that in your company, they likely won’t take the risk. That’s why a lot of co-located companies underestimate the talent pool. Not only does it help them rationalize their chosen way of working, but by dipping their toe in, they really don’t see the quality candidates that a remote-first company does.

Our goal is that when a super talented person wants to work remotely, Help Scout is in their top five. No doubt we have stiff competition with great companies like Zapier, Automattic, Buffer, Trello, and Basecamp, but we invest significant time and resources to remote culture to be among those top choices.

Change the hiring process

When I lived in Boston, I noticed that a talented person would be on the market for a matter of days before being scooped up. It’s incredibly competitive, and in my experience, it’s easy to make mistakes when hiring this quickly.

Hiring remotely is different. On average it takes us about 40 days to fill a role and roughly three weeks for a candidate to go through the full process. Every role includes a project, which is designed for the person to spend 4-8 hours showing us what they can do (remotely, of course). We like to go back and forth, giving folks critical feedback and simulating what it will be like to work together.

A longer hiring process is also a wonderful candidate experience. It gives both sides a lot of time to carefully consider whether this is a perfect fit, and it gives the candidate the chance to get to know several people on the team. When the process is more thorough and involves more people, it’s also easier to steer clear of unconscious bias. I can only remember one time in seven years that we lost out on someone for not moving fast enough. That’s a risk we’re willing to take in favor of making the right decision.

For more on our hiring process, listen to Help Scout’s VP of Engineering, Megan Chinburg, on the Outside the Valley podcast. Megan covers the process start to finish, including the “value screening” stage and how we work to reduce biases in the interview process.

Recruit to diversify the hiring pool

The data is abundantly clear: Diverse companies are more successful. As noted in our first Diversity and Inclusion report (we’ve made significant progress since then that we’ll share soon), we do proactive recruiting to even out the hiring pool. Without proactive efforts to make the applicant pool a reflection of the general population, it’s almost impossible to build a team with varied opinions, perspectives and experiences.

Unfortunately this wasn’t always a focus for us, and we had significant “diversity debt” to account for when this became a priority in 2016. But I can say that changing the candidate mix in our hiring pool has transformed our team in unbelievably positive ways. Becca Van Nederynen and Leah Knobler from our People Ops team deserve tremendous credit for pushing this effort forward on our behalf.

Why am I talking about this in an essay on remote culture? Because every team needs to be doing it if they want to build a great business. As a remote team, by way of having a larger talent pool, your opportunity to hire people from underrepresented groups is far greater. It’s important to make the most of that opportunity and to hire a recruiter to source diverse candidates as soon as you can.

Investing in remote team culture

Remote or not, the culture you build is a direct result of the time and effort you put into it. In hindsight, one of the smartest things we’ve done as a company is invest in People Ops. Compared to co-located cultures, we’ve always needed a disproportionate number of people focused 100% on the team and the culture. We had a two-person People Ops group at 20 people, and today (at 75 people), we have three people on the team.

A lot of the issues faced by co-located companies at 50, 75 and 100 people actually have to be addressed in a remote culture at 10, 20 and 35. For Help Scout, those smaller numbers were much more challenging than growing to 50 and 75 people.

Another common misconception is that remote teams don’t scale. But we don’t have to worry about office space, the talent pool is always large enough, and we addressed a lot of the structural and communication challenges early on.

Our retention and engagement numbers show the ROI of our investment in the culture over the years. In our history, we’ve hired 92 people and only five have left voluntarily.

(Three of those five were already on a performance plan of some sort and were likely going to need a different fit anyway.)

While we are working to improve areas such as cross-team communication and acting when someone isn’t delivering, our other employee engagement numbers speak for themselves:

In areas such as Management, Leadership, Work/life balance, and Feedback & recognition, I’m especially proud of what we’ve accomplished as a remote team. It’s incredible to see 98% of people strongly agree that their manager genuinely cares about their wellbeing.

I mentioned that different work philosophies aren’t right or wrong; they merely have different tradeoffs. There are two common remote tradeoffs that we have to be very intentional about:

Building relationships

In a remote culture, it’s easier to get a productive 4-6 hour block of work done during the day. But one of the tradeoffs you make is that it’s not natural to develop close relationships with your teammates. Aside from work-related discussion, there are no social outings, no casual lunch conversations, usually no friendships that also exist outside of the workplace.

Whereas relationships come naturally in a co-located culture, you have to work at it remotely. We spend a bunch of time on relationship-building, hosting semi-annual company retreats and quarterly leadership off-sites, and we use video services like Zoom and Appear.in.

Coaching

I mentioned earlier that it’s harder to be a manager in a remote culture, and I’ve only realized this in the last year. I’m a huge believer in the Players and Coaches philosophy, which dictates that people be in a dedicated Player (individual contributor) or Coach (manager) role. Player-Coach (a little of each) doesn’t really allow someone to be at their best, and this is magnified exponentially in a remote workplace.

It’s a lot more time-consuming for Coaches on a remote team to keep up with all the information streams. Someone is always working, even when you sleep. In a co-located company you may have a morning stand-up meeting for 15 minutes. In our company, stand-ups are written updates in Slack, and they appear at all hours of the day. I’m sure it’s easy to see how having people working all hours of the day can create an additional burden for Coaches. So we try to make it so that Coaches have no fewer than four and no more than 10 direct reports.

While it’s more challenging to be a Coach, the tradeoff is that Players really shine in a remote company if you do it right. The right culture and Coaching can free up a Player to do measurably better work if they are remote. Fewer interruptions really are a magical thing in today’s workplace.

FAQs about remote company culture

Where can I read more about building a remote team?

I highly recommend the book Remote: Office Not Required, by Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson of Basecamp. They’ve been blogging about this for more than a decade and are a sincere inspiration to us.

Do you pay people differently based on geography?

No. Any remote company will tell you that it gets super complicated, and great work has the same value to the company, so we should be happy to pay the same amount of money for it. Our salary formula is internally public to employees, and it’s the same no matter where you live.

Is there a cost savings?

No. What we save on office space, we spend on company retreats. Our overall headcount is lower because we only hire high performers, but the average salary is higher than most tech companies. (We seek high performers for the team, and it’s only fair to pay them like high performers.) When it comes to benefits, we work hard to give people inside and outside of the U.S. equal treatment. If your primary motivation for experimenting with remote is cost savings, don’t waste your time.

What other questions do you have? We’d love to hear them.